Epigenetics: “The Sins of the Fathers” and the Ten Commandments, Behaviors beyond Neo-Darwinism

The biblical concept, particularly within the context of the Ten Commandments, serves as a profound moral and social guide. It warns that actions have consequences extending beyond the individual actor, rippling through families and communities.

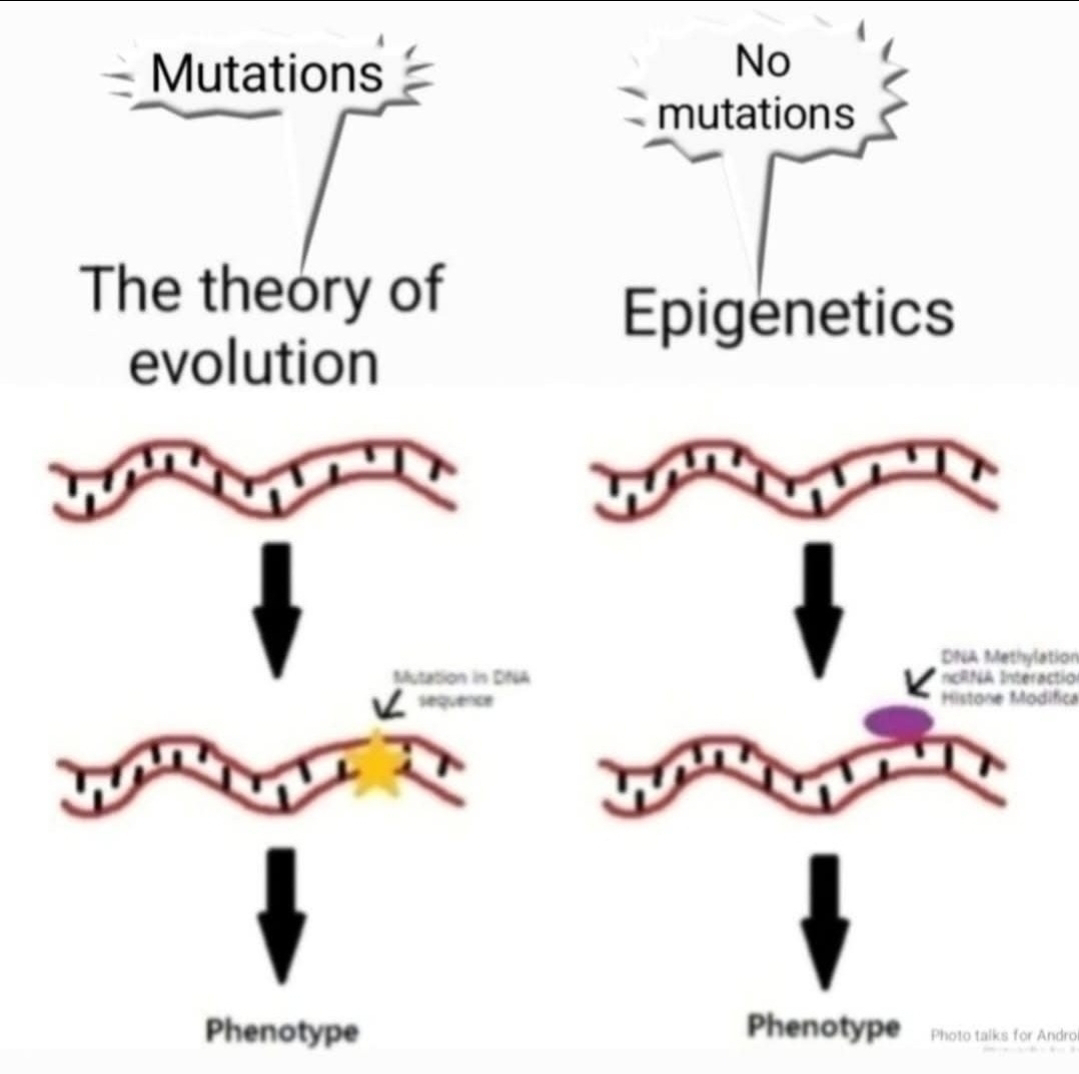

Behaviors deemed detrimental—idolatry, diet, crime, adultery, disobedience, extends metaphorically to lifestyles involving poor diet, chronic stress, or exposure to toxins—were understood to impact not just the individual's relationship with the divine or their community, but also the well-being of their progeny. This wasn't necessarily seen solely as supernatural punishment, but could also reflect an ancient observation of recurring patterns within families – patterns of health, behavior, and misfortune that seemed to follow generational lines. The commandment, therefore, implicitly advocates for responsible living, not merely for personal salvation or social standing, but for the flourishing of future generations. It underscores a deep interconnectedness and a long-term view of responsibility.Enter epigenetics. This field studies changes in organisms caused by modification of gene expression rather than alteration of the genetic code itself. Unlike Neo Darwinian mutations, which change the DNA sequence (the letters in the book of life), epigenetic modifications act more like annotations, bookmarks, or highlighting, influencing how, when, and to what degree specific genes are read and translated into proteins, without changing the underlying text.

Key epigenetic mechanisms include DNA methylation (adding chemical tags, often methyl groups, to DNA, typically silencing genes) and histone modification (altering the proteins, histones, around which DNA is wound, making genes more or less accessible for transcription)Crucially, these epigenetic marks are not static; they can be profoundly influenced by environmental factors throughout an organism's life. Diet, stress levels, exposure to pollutants or toxins, parental care, and traumatic experiences can all leave epigenetic signatures. For example, severe nutritional deprivation or chronic stress in a parent can alter methylation patterns or histone modifications in their germ cells (sperm and eggs).The astonishing implication, supported by growing evidence in animal models and some human cohort studies (like those examining descendants of individuals who experienced famine, such as the Dutch Hunger Winter), is that these environmentally induced epigenetic modifications can sometimes be transmitted across generations.This is known as transgenerational epigenetic inheritance.

This is where the ancient concept and modern science converge. The "sins" – the poor lifestyle choices, exposure to harsh environments, or traumatic experiences of the fathers (and mothers) – can potentially lead to epigenetic changes that are passed down, influencing the health, stress responses, metabolism, or even behavior of their children and grandchildren. A father's high-fat diet before conception, a grandparent's exposure to certain toxins, or a parent's experience of significant trauma might subtly alter the gene expression patterns in their offspring, potentially predisposing them to metabolic disorders, heightened anxiety, or other conditions. This provides a biological mechanism for how the consequences of one generation's life experiences could be "visited upon" subsequent generations, echoing the ancient biblical observation.

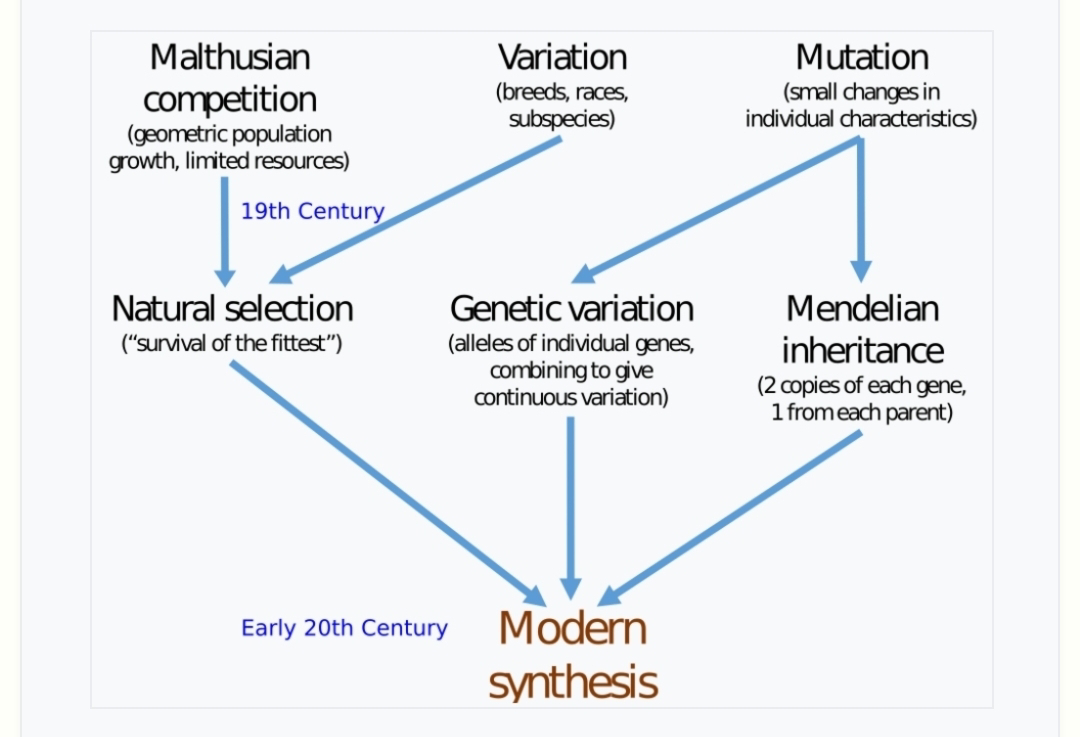

This emerging understanding significantly challenges the framework of neo-Darwinism (also known as the Modern Synthesis). Neo-Darwinism posits that evolution primarily occurs through random genetic mutations generating variation, upon which natural selection acts, favoring traits that enhance survival and reproduction.

Inheritance, in this view, is almost exclusively mediated by the transmission of DNA sequences. Changes happen gradually over long timescales.Epigenetics introduces several complicating factors:

Directed Variation: Epigenetic changes are often direct responses to environmental cues, rather than purely random occurrences like DNA mutations. This hints at a more responsive, potentially adaptive layer of inheritance.

Rapid Inheritance of Acquired Traits: Epigenetics allows for environmentally induced traits (phenotypes) acquired during an organism's lifetime to be potentially passed to offspring relatively quickly, sometimes within a single generation.

This resonates with Lamarckian ideas (inheritance of acquired characteristics), which were largely dismissed by the Modern Synthesis. While epigenetic inheritance is often less stable than genetic inheritance and may fade over generations, its existence provides a faster route for environmental information to influence inherited traits.

Beyond the Gene: It emphasizes that inheritance is more complex than just the DNA sequence. The "epigenome"—the collection of all epigenetic marks—represents another layer of heritable information that interacts dynamically with the environment.

Epigenetics significantly challenges core principles of neo-Darwinism, such as the roles of mutation and natural selection. It adds significant complexity. It suggests that evolution operates on multiple levels and timescales, incorporating not only slow genetic changes but also faster epigenetic adjustments that mediate the interplay between an organism's fixed genome and its fluctuating environment. It highlights that the environment doesn't just act as a selective pressure on random variation; it can actively shape the heritable information passed between generations in non-random ways.

In conclusion, the ancient biblical warning about the "sins of the fathers" carrying forward through generations finds an unexpected and compelling echo in the modern science of epigenetics. While the biblical text framed this in moral and theological terms, epigenetics provides a potential biological mechanism: parental experiences and environments can leave inheritable marks on gene expression, impacting descendants' biology. This discovery not only bridges ancient wisdom and contemporary science but also enriches our understanding of inheritance, forcing a reappraisal of the strictly gene-centric view of neo-Darwinism and opening new avenues for understanding health, disease, and the intricate dance between nature, nurture, and the legacies we leave behind.

Comments

Post a Comment